Try to See It from My Angle: The Bermuda Triangle – What is it about this infamous stretch of ocean (and sky) that causes ships and planes to vanish without a trace?

At ten past two in the afternoon of 5 December 1945, five US Navy Avenger torpedo bombers took off from the naval air station at Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The commander of Flight 19, Lieutenant Charles Taylor, had been assigned a routine two-hour training flight of fifteen men on a course that would take them out to sea sixty-six miles due east of the airbase, to the Hen and Chicken Shoals.

There the squadron would carry out practice bombing runs, then fly due north for seventy miles before turning for a second time and heading back to base, 120 miles away. Their plotted flight plan formed a simple triangle, straightforward to execute, and Lieutenant Taylor and his four trainee pilots headed out into the clear blue sky over a calm Sargasso Sea.

Even though everything seemed set fair, some of the crew were showing signs of anxiety. This was not unusual during a training flight over open water. Less usual was the fact that one of the fifteen crewmen had failed to show up for duty, claiming he had had a premonition that something strange would happen on that day and that he was too scared to fly.

And, within a few minutes after take-off, something strange did happen. First, Lieutenant Taylor reported how the sea appeared white and ‘not looking as it should’. Then, shortly afterwards, his compasses began spinning out of control, as did those of the other four pilots, and at 3.45 p.m., about ninety minutes after take-off, the normally cool and collected Taylor contacted Lieutenant Robert Cox at Flight Control with the worried message:

‘Flight Control, this is an emergency. We seem to be off course. We can’t make out where we are.’

Cox instructed the pilot to head due west, but Taylor reported that none of the crew knew which way west actually was. And that too was highly unusual as, even without compasses and other navigational equipment, at that time of day and with the sun only a few hours from setting, any one of them could have used the tried and tested method of looking out of the window and following the setting sun, which will always lie to the west of wherever you find yourself.

Just over half an hour later, Taylor radioed Flight Control again, this time informing them he thought they were 225 miles north-east of base. His agitated radio message ended with him saying, ‘It looks like we are …’ and then the radio cut out.

By then they would have been desperately low on fuel, but the five Avengers had been designed to make emergency sea landings and remain afloat for long enough to give the crew the chance to evacuate into life rafts and await rescue.

A Martin Mariner boat plane was immediately sent out to assist Flight 19 and bring the men back; but as it approached the area in which the stricken crew were thought to have been lost, it too broke contact with Flight Control. None of the aircraft and none of the crew were ever found and the official navy report apparently concluded that the men had simply vanished, ‘as if they had flown off to planet Mars’.

To this day, the American military has a standing order to keep a watch for Flight 19, as if they believed it had been caught up in some bizarre time warp and might return at any time.

At least, that is how the story goes. And it would have had a familiar ring for some, as it wasn’t the first time a mysterious disappearance had been reported in the area. On 9 March 1918, the USS Cyclops left Barbados with a cargo of 10,800 tons of manganese (a hard metal essential for iron and steel production) bound for Baltimore on the east coast of America.

The following day, Lieutenant Commander G. W. Worley, a man with a habit of walking around the quarterdeck clad in nothing but his underwear and a hat and carrying a cane, reported how an attempted mutiny by a small number of the 306-man crew had been suppressed and that the offenders were below decks in irons.

And that was the last anybody ever heard from Captain Worley or any of his crew. The 20,000-ton Cyclops simply vanished from the surface of the sea, into thin air.

The conclusion at the time was the ship had been a victim of German U-boat activity, but when investigations in Germany after the end of the First World War revealed that no U-boats had been located in the area, that theory was ruled out.

Instead, speculation ranged from the suggestion – proffered quite seriously – by a popular magazine that a giant sea monster had surfaced, wrapped its tentacles around the entire ship, dragged it to the ocean bed and eaten it, to the rumour, UFO hysteria in full swing (see ‘The Famous Aurora Spaceship Mystery’), that the vessel had been lifted, via giant intergalactic magnets, into outer space.

And then, in 1963, eighteen years after the disappearance of Flight 19, it happened again. The SS Marine Sulphur Queen was on a voyage from Norfolk, Virginia, to Belmont in Texas. On 3 February, the ship radioed a routine report to the local coastguard to give her position: she was, at the time, sailing close to Key West in the Straits of Florida.

Shortly afterwards she vanished. Three days later the coastguard, searching for any sign of the missing vessel, found a single life jacket floating in the sea. Since then, no other evidence of the Marine Sulphur Queen, its cargo or the 39-man crew has ever been found.

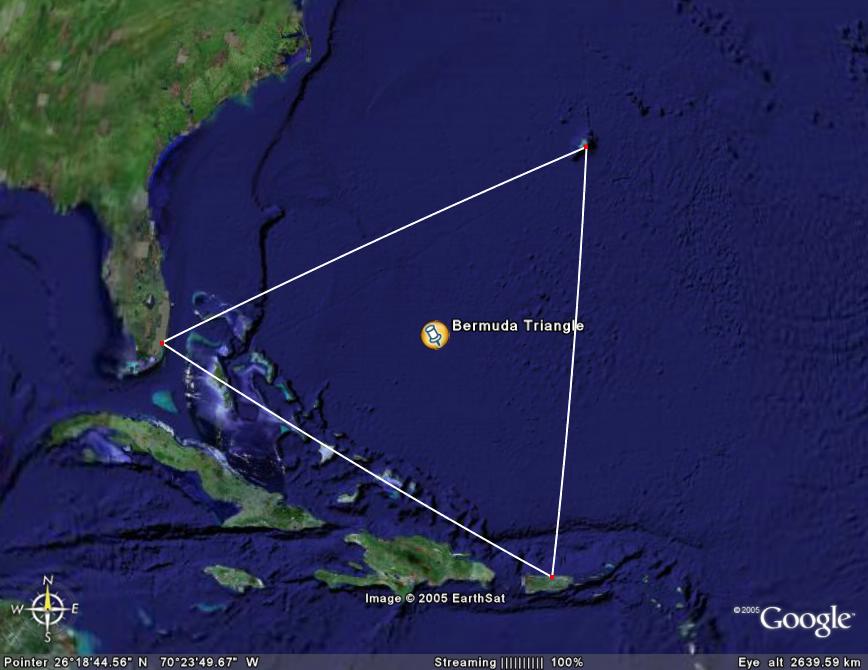

Back in 1950, connections had already been made between the disappearance of Flight 19 and of the USS Cyclops: reporter E. V. W. Jones was the first to suggest mysterious happenings in the sea between the Florida coast and Bermuda. Two years later, Fate Magazine published an article by George X. Sand in which he suggested that the mysterious events – thousands of them, by his calculation – had taken place within an area that extended down the coast from Florida to Puerto Rico and in a line from each of these to Bermuda, creating what he called a ‘watery triangle’.

His views were shared by one Frank Edwards, who published a book in 1955 called The Flying Saucer Conspiracy in which he claimed that aliens from outer space were also operating in the same area; hence the sky was incorporated into the ‘watery triangle’, which became known as the ‘Devil’s Triangle’.

In 1963, following the disappearance of the Marine Sulphur Queen, journalist Vincent Gaddis wrote an article for Argosy magazine in which he drew together the many mysterious events that had taken place within the triangular area of sea and sky.

This proved so popular that he expanded the article into a book, which he called The Deadly Bermuda Triangle, thereby coining the famous expression that was to become synonymous with unexplained disappearances the world over.

Extract from Mysterious World

Eleven years later, a book by former army intelligence officer Charles Berlitz, simply entitled The Bermuda Triangle, sold over 20 million copies and was translated into thirty different languages. In 1976 the book won the Dag Hammarskjöld International Prize for non-fiction and the world became gripped by Bermuda Triangle fever – and has been ever since.

But it is worth noting that even as recently as 1964 the Bermuda Triangle, as we now know it, simply did not exist.

Geographically, the Bermuda Triangle covers an area in the western Atlantic marked by, at its three points, Bermuda, San Juan in Puerto Rico and Miami in Florida – although, on closer study of the locations of some ocean disasters attributed to the myth, it would be easy to extend that area halfway round the world.

The Mary Celeste, for example, has even been connected to the Bermuda Triangle, which would extend its boundaries closer to Portugal!

But could there be any truth in the myth – some more prosaic explanation to account for the seemingly paranormal events? Is there anything about the actual geography of the area that might cause so many ships and aircraft to vanish apparently without a trace?

To start with, the sea currents in the area are heavily affected by the warm Gulf Stream that flows in a north-easterly direction from the tip of Florida to Great Britain and northern Europe. The warm current divides the balmy water of the Sargasso Sea and the colder north Atlantic and is why the climate in northern Europe is much more moderate than might be expected, considering that Canada and Moscow are as far north as England.

Once leaving the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf Stream current reaches five or six knots in speed and this affects the heavy shipping in the area in many ways, including navigation.

Inexperienced sailors, especially in the days before radar and satellite navigation, could very easily find themselves many miles off course after failing to measure the ship’s speed with sufficient accuracy, especially in the days when this was calculated by throwing from the bow of the ship a log attached to a rope and timing the appearance of each of a series of knots in the rope as it passed the stern.

Failing to do this often enough while sailing in the fast-moving Gulf Stream could quite speedily lead to the crew of a ship becoming hopelessly lost in the vast Atlantic Ocean. Another effect of the fast-moving current would be to scatter the wreckage of lost ships and aircraft over a vast area, many miles from the site of an accident, making it well nigh impossible for rescue teams to locate survivors.

Then there is the North American continental shelf which is responsible for the clear blue water of the Caribbean Islands. After only a few miles, the shelf gives way to the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean, an area known as the Puerto Rico Trench. And at over 30,000 feet deep, nobody has ever been down there to clear up any mysterious disappearances.

And furthermore, the continental shelf is home to large areas of methane hydrates (methane gases that bubble up through the water after being emitted from the seabed). Eruptions from any of these in the relatively shallow waters cause the sea to bubble and froth, affecting the density of the water and hence the buoyancy of vessels travelling on its surface.

Scientific tests have shown that scale models of ships will sink when the density of the water is sufficiently reduced, which could account for the sudden disappearance of various craft within the area. Added to which, any wreckage might be carried away by the Gulf Stream and scattered across the Atlantic in no time at all.

The Bermuda Triangle is also known to be an area of magnetic anomalies, or unusual variations in the earth’s magnetic field. Indeed this area of ocean is one of the two places on earth where a magnetic compass points to true north (determined by the North Star) rather than magnetic north (located near Prince of Wales Island in Canada).

The only other place where true north lines up with magnetic north is directly on the other side of the planet, just off the east coast of Japan, an area known by Japanese and Filipino seamen as the ‘Devil’s Sea’. In both these areas, navigators not allowing for the usual compass variation between true and magnetic north will become hopelessly lost, and mysterious disappearances are equally common in the Devil’s Sea.

But locals there do not blame UFOs or sea monsters; they blame human error. Christopher Columbus, the famous fifteenth-century navigator credited with ‘discovering’ the Americas, was one of the first people to recognize the difference between true and magnetic north; and he wasn’t at all fazed by the odd compass readings he seemed to be getting as he sailed between Bermuda and Florida over five hundred years ago.

Magnetic anomalies are also thought to be responsible for the fog that appears to cling to aircraft and boats in the Bermuda Triangle and Devil’s Sea. In such cases, the fog gives the strange illusion that it is travelling along with the craft rather than that the vessel is travelling through it, creating a ‘tunnelling’ effect for the passengers on board. Many reports have been made of the disorientating effect of this curious fog.

In one of the most celebrated instances, the captain of a tug towing a large barge reported that the sea was ‘coming in from all directions’ (due to methane hydrates, no doubt) and that the rope attached to the barge plus the barge itself, only a few yards behind the tug, appeared to have completely vanished, presumably shrouded in magnetic fog.

Another natural phenomenon that might be held responsible for the strange disappearances in the region are hurricanes, notorious in the area of ocean between Bermuda and the Gulf of Mexico, in the middle of which lies the Bermuda Triangle.

These must take their fair share of the blame in bringing down small aircraft and swallowing boats, sending the wreckage to the floor of the Atlantic in minutes and leaving no trace of the craft on the surface.

So what really happened in the case of Flight 19, the USS Cyclops and the Marine Sulphur Queen? Let’s examine the first of these disappearances in a bit more detail. Squadron Leader Lieutentant Charles Taylor, although an experienced pilot, had recently been transferred to the air station at Fort Lauderdale and was new to the area.

Added to which, he was a known party animal and had been out drinking the evening before the fateful day.

A very hungover Taylor then tried to find someone else to take over as leader of the training flight – the only point of which was to increase the flying hours of the four apparent novices – but no other pilot would agree to stand in at such short notice.

Shortly into the flight, Taylor’s compass malfunctioned and, unfamiliar with the area, he had to rely on landmarks alone. After nothing but open sea, the aircraft eventually flew over a small group of islands Taylor thought he recognised as his home – Florida Keys.

Flight 19 was in constant touch with Flight Control and was told to head directly north which, Taylor thought, would take him straight back to base. But Flight 19 was not over Florida Keys in fact; it was over the Bermudan Islands – exactly where it should have been.

Heading north simply sent the stricken aircraft out into the open Atlantic. Crew members were heard to suggest to each other they should immediately head west, as their compasses were actually working, but none of the trainees dared to contradict their leader.

With a storm gathering and the sun not visible through the cloud, Taylor refused to listen to his subordinates, accepting the instruction from Flight Control instead. But when told to switch to the emergency radio channel, Taylor declined, stating that one his pilots could not tune in to that particular channel and that he did not want to lose contact with him.

As a result of this, contact between Flight 19 and Fort Lauderdale became increasingly intermittent.

After an hour of flying due north, and with no land in sight, Taylor reasoned he must be over the Gulf of Mexico, and with that made the right-hand turn, due east, he thought would bring his team back to the west coast of Florida.

But instead, an hour north of Bermuda and flying over the Atlantic with Flight Control believing them to be close to the Gulf, this manoeuvre only served to take them further out to sea.

Flight 19, miles away from where anybody believed them to be, would then have run out of fuel, ditched into the sea beyond the continental shelf, and been broken within minutes by the storm. The Mariner sent to look for them was, in fact, one of two that were sent to assist. The first arrived back at base safely but the second exploded shortly after take-off. (The Mariners, notorious for fuel leaks, were nicknamed ‘flying gas tanks’.)

Radio contact had been lost twenty-five minutes into the flight and debris floating in a slick of spilt oil was found in the exact location the plane was though to have come down.

In short, there was nothing mysterious about the accident after all. The official report at first stated that flight leader error was to blame for the loss of Flight 19, but this was then changed to ‘cause unknown’, giving rise to the mystery. Contrary to the fictitious version of events, nobody has ever stated, in an official capacity, that the aircraft simply vanished ‘as if they had flown off to planet Mars’.

Extract from Mysterious World

The disappearance of the USS Cyclops does remain a mystery, however, although heavy seas and hurricanes were reported in the area at the time. It is now thought that a sudden shift in its eleven-thousand-ton metal cargo was to blame, causing the ship to capsize with all hands on deck and sink to bottom of the ocean.

In the case of the SS Marine Sulphur Queen, something Triangle enthusiasts rarely mention is that the cargo was made up of 15,000 tons of molten sulphur sealed in four giant tanks and kept at a heat of 275 degrees Fahrenheit by two vast boilers connected to the tanks via a complex network of coils and wiring.

They also do not tell us that the T-2 tankers such as the Marine Sulphur Queen had a terrible record for safety during the Second World War and that within the space of just a few years three of them had previously broken in half and sunk.

Indeed, a similar sulphur-carrying ship had vanished in 1954 under less mysterious circumstances, having spontaneously exploded before any distress call could be made.

But what clinches it for me is one particular detail: the fact that officers on a banana boat fifteen miles off the coast of San Antonia near Cuba reported a strong acrid odour in the vicinity.

The conclusion at the time, but overlooked later by Triangle enthusiasts, was either that leaking sulphur must have quickly overcome the entire crew and a spark then ignited the sulphur cloud, causing a fire that the unconscious crew were unable to put out, or that an explosion had torn through the boat, depositing the crew in the shark- and barracuda-infested waters.

Either way, investigators decided the ship must have gone down just over the horizon from the banana boat whose crew had detected the sulphurous odour.

In addition to natural phenomena, there are man-made ones to consider too when it comes to the Bermuda Triangle. Indeed, the Caribbean and southern Florida have long been a favourite haunt for pirates and it’s not exactly in their interests to report the ships they’ve sunk after looting their cargo or crew they’ve murdered in the process.

Many unexplained disappearances would be far better explained by pirate activity than by extraterrestrial abduction or sea monsters lurking in the deep. The pirates of the Caribbean were not heroes but vicious murderers who took no prisoners and left no evidence of their piracy, and don’t let Johnny Depp or Keira Knightly seduce you into thinking otherwise.

The main explanation for the mysterious events of the Bermuda Triangle is sheer invention. Indeed there are many examples of writers bending facts to suit their stories (notably in the case of the Loch Ness Monster and the Mary Celeste) or indeed pretty much every story I’ve covered in this book), which is hardly surprising since mysterious and ghostly goings-on can be very profitable (as I hope to find out), as everyone loves a good mystery.

One of my favourite examples of this is the story of the incident in 1972 of the appropriately named tanker V. A. Fogg that was said to have been found drifting in the Triangle without a single crew member aboard.

Everybody had vanished apart from the captain whose body was found sitting at his desk with a steaming mug of tea in front of him and a haunted look upon his face. He had died from shock – or so the story goes.

The truth is rather different, although not lacking in drama. The V. A Fogg had just delivered a cargo of benzene at the Phillips Petroleum Depot at Freeport in Texas. As it returned through the Gulf of Mexico with its skeleton crew (and I mean that metaphorically in case you’ve still got those Caribbean fellows on your mind) cleaning out the fuel tanks, the ship suddenly exploded and sank.

The blast created a 10,000-foot-high pall of smoke and, on further investigation, the US Coastguard found the vessel broken in two on the seabed, one hundred feet below the surface.

Their photographic record, including the bodies recovered from the sea, is at complete odds with the story told for the benefit of the Bermuda Triangle mystery, plus, of course, the Gulf of Mexico is not even in the Bermuda Triangle. I don’t mean to be a mystery-buster, but we do need to get our facts straight.

To resolve the mystery of the Bermuda Triangle once and for all, I decided to adopt my fail-safe research method of getting to the bottom of things – finding out who has the most money at stake. I don’t mean documentary makers, newspapers or television companies; I’m talking about the insurance industry.

Because it is very much in their interests to have carried out meticulous research into accidents at sea, we can be fairly certain that they will have looked into any so-called mysteries with considerable care.

Starting with the largest, and oldest, shipping insurance company in the world, Lloyds of London, we discover that they certainly did take notice of the Bermuda Triangle reports during the early 1970s and issued a statement to Fate Magazine, published on 4 April 1975.

The statement declared that ‘428 vessels have been reported missing throughout the world since 1955 and that there is no cause to suspect the Bermuda Triangle is swallowing more ships then any other section of the oceans’.

So if Lloyds of London believe there is no mystery to be found in the Bermuda Triangle, then nor should we. But, just in case people with minds immeasurably greater than ours are wrong, or even lying to us, then let’s do a few calculations of our own. We could start by considering that the surface of the earth comprises 71 per cent water, an area of 13,900,000 square miles.

The Bermuda Triangle at its smallest – , depending on which author you believe, as many extend the area to cram as many disappearances into their version of the Triangle as possible – is around 500,000 square miles so that is about 3.6 per cent of the world’s sea area.

During the last century over fifty ships, large and small, and twenty aircraft of all shapes and sizes have come to grief in the Bermuda Triangle. If we use those figures and apply the same principle across the planet, we should expect to have lost around two thousand aircraft and boats in total over the last one hundred years, which sounds a little too high.

But are twenty accidents per year, small or large, around the world, unreasonable to imagine? Are the events attributed to the Bermuda Triangle any greater in number than they would be in any other section of the ocean of comparable size?

Other mystery makers point to the statistic of one thousand craft lost in the Bermuda Triangle since records began. But they fail to remind readers that records began many centuries ago when Christopher Columbus first sailed west in 1492, which works out at an average of less than two disappearances per year. That sounds about right to me.

That combined with the fact that coastguards have known the reason for the loss of a craft in almost every case – if people would only bother to ask them – should stop the fuss once and for all. This isn’t an unusually high percentage of accidents for this area at all in comparison with other parts of the world.

The only real surprise is that Lloyds made any statement at all – if they’d kept quiet, they could have put their premiums up for shipping in that now infamous stretch of sea. – Albert Jack

Albert Jack AUDIOBOOKS available for download here

Albert Jack’s Mysterious World