The Mysterious Death of God’s Own Banker – Did Roberto Calvi, head of a bank with close connections to the Vatican, take his own life or was there a more sinister reason why he was found hanging under Blackfriars Bridge?

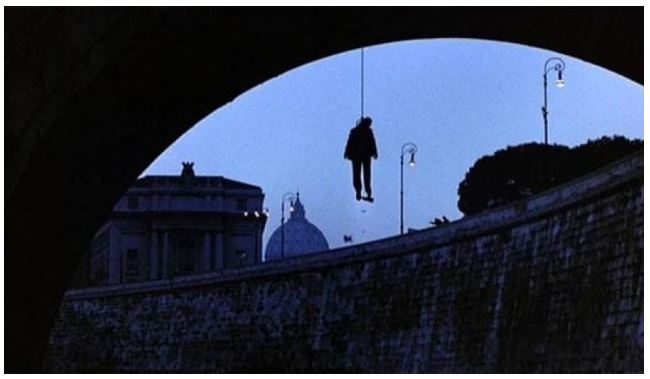

Early in the morning of 18 June 1982, in a scene redolent of a real-life Da Vinci Code, the body of Roberto Calvi, chairman of one of Italy’s most influential financial establishments, the Banco Ambrosiano, was found hanging from scaffolding under London’s Blackfriars Bridge by a passing postman.

Calvi’s pockets were full of stones and, bizarrely, a brick had been pushed into the zip of his trousers. The smartly dressed banker was carrying nearly £10,000 in cash in three different currencies in his jacket pocket – lire, Swiss francs and pounds sterling.

The man who provided banking facilities for the Vatican, earning him the media nickname of ‘God’s Banker’, had, apparently taken his own life.

It seemed pretty clear to most people that he had committed suicide, but had he? Others were far more doubtful, especially on discovering that Calvi was supposed to have been in Milan at the time. Indeed his passport was back there, and he had made no plans to travel to London at all.

Milan was where Roberto Calvi had been born, on 13 April 1920, just as Europe was recovering from the aftermath of the Great War.

It was at the end of the Second World War that Calvi joined the Banco Ambrosiano, becoming gradually promoted within the organization and, in the mid 1960s, acquiring the patronage of an important shareholder, Sicilian-born Michele Sindona, known to his associates as ‘the Shark’.

Sindona had begun his working life as a tax accountant, but he soon switched to less law-abiding pursuits and began to assist his Sicilian associates in their smuggling operations. When he moved to Milan, he quickly impressed Mafia bosses with his tax-avoidance skills and in 1957 started work with the Gambino family by managing their growing profits from heroin smuggling.

By the end of the first year, Sindona had not only actually bought his first bank, but he had also become firm friends with Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, who was among those who grew to rely upon the Sicilian’s financial acumen, profiting considerably from it.

By the time Montini became pope in 1963, Sindona had enlarged his Mafia-related banking empire. In 1968 he began moving vast sums through the Vatican Bank, which operated outside Italian law, to secret Swiss bank accounts. He had made himself indispensible to the Mob while somehow managing to retain an air of innocent respectability, even being named ‘Man of the Year’ in 1974 and widely regarded as the ‘saviour of the lira’.

Throughout this time, Sindona had been grooming Calvi as his natural successor. He even introduced him to Propaganda Due, a powerful Masonic lodge, also known simply as P2, before Calvi was appointed chairman of the ailing Banco Ambrosiano in 1971. And with that appointment, Roberto Calvi had joined the Shark in highly infested waters.

The maverick P2 Masonic lodge in Milan was formed in 1877; by the 1960s and 70s it was regarded by some as something of a state within a state, and by others as a shadow government.

Its members formed an elite of nine hundred influential Italians, including forty-three members of parliament, nineteen of the top judges and magistrates, fifty-eight university professors, forty-eight military generals, the heads of the Italian secret service, key banking regulators, important civil servants tasked with running government enterprise, and leading Italian businessmen, including the man who was to become the most powerful Italian since Julius Caesar, Silvio Berlusconi.

During the Cold War, members of P2 genuinely believed they could form an underground government in opposition should Communism take hold of their country. Vatican officials and the Mafia were also thought to have a large representation at the lodge. Now, not wishing to wake up with a horse’s head in my bed, I am going to proceed with rather more caution from here onwards.

Through his association with P2 and its grand master, Licio Gelli, Calvi began to transform the small-time Milanese bank into a big player of international repute, and he soon found himself dining with princes and kings. With such influential and powerful new friends, Calvi took very little time in establishing the Banco Ambrosiano as an important financial institution.

Beneath its respectable surface, however, Calvi’s bank was taking the lead in an international money-laundering business. During the early 1970s, it began establishing shell companies all over the world, moving vast sums of money between them in a range of deals brokered by Gelli for his P2 network.

As the profits from drug smuggling grew and the money flowed in, Roberto Calvi’s laundering activities increased while the powerful Gelli kept a watching brief, making deals and keeping records. Then in 1974 disaster struck.

In April that year, a sudden and unexpected stock market crash, known as ‘Il Crack Sindona’, destroyed most of Sindona’s banking empire, with profits falling by as much as 98 per cent in some cases. Sindona personally lost over $40 million and he was struggling to keep control of his network when one of his investments, the Franklin Bank, was declared insolvent.

Charges were then brought against Sindona relating to fraud, mismanagement and poor loan policies. When Francesco Mannoia, a Mafia member turned police informer, testified that much of Sindona’s money consisted of the proceeds of heroin trafficking, the Gambino family, determined to see the return of their ill-gotten gains, turned to Calvi and his Banco Ambrosiano and put pressure on them.

More – Albert Jack’s Mysterious World

Further intrigue followed when the Holy See, part of the Vatican business organization, was said to have lost $40 dollars themselves during Il Crack Sindona, placing the Vatican quite clearly in the same boat as the Mafia drug lords, whether they realized it or not.

By the close of the 1970s, Roberto Calvi was in the thick of the action, and busy setting up shell companies in Panama and the Bahamas. In 1980, no doubt in recognition for his good service, Calvi was enrolled in P2 as a full member and immediately began atoning for the mistakes of his predecessor Michele Sindona in an attempt to return some of the money lost during the banking disaster of 1974.

Banco Ambrosiano became a clearing house for politicians and businessmen alike who wanted to buy protection from government officials or American law enforcers, who were, by now, taking a close interest in Italian drug traffickers.

Licio Gelli acted as deal broker and Roberto Calvi was tasked with finding a means of spiriting millions of dirty dollars away from the reach of investigators and returning them as legitimately earned income. The aborted takeover of the Rizzoli Group during 1980 was in fact a cover for one of these money-laundering deals.

The idea was that Calvi, Gelli and other powerful members of P2 would buy up a controlling number of Rizzoli shares and deposit them with Rothschild Bank in Zurich. Calvi then arranged for his bank to lend $142 million to a Panama-based company called Bellatrix.

The mysterious company, which later turned out to exist in name only, then bought Rizzoli shares at ten times their value, generating a huge income for P2 members and investors and filling their Swiss accounts.

When Rothschild executives realized what exactly was going on, they were alarmed to find they had been caught up in the transaction without their knowledge. According to one executive director, he was told by a senior board official that ‘we have to find a way out of this or I may end up in Lake Zurich’.

But within a few days, the windfall profits had been released into the accounts of the P2 organizers of the deal that Roberto Calvi had facilitated, at which some of them, key Calvi allies, immediately fled Italy, financially secure for life.

Calvi was now heavily involved in the banking/political/ religious/criminal melting pot that featured in every part of the Italian way of life during the 1960s and 70s, and many mysterious disappearances that took place during that era have remained unsolved. Indeed, knowing he knew something about everything, Calvi was becoming increasingly concerned for his own safety, paying up to 4 million lire a day for a personal armed guard and bullet-proof car.

He had become further alarmed when, in 1978, Pope Paul VI died and was replaced by Pope John Paul I. By then Vatican officials had resolved to clean up their image. As soon as Pope John Paul I had taken office, he took the unprecedented step of ordering Vatican books and records to be opened for scrutiny, pledging to end corruption and fraud.

More – Albert Jack’s Mysterious World

He also announced he intended to modify the Catholic Church’s position on the use of contraception. Sadly, John Paul I died within thirty-three days of becoming pope, officially of a heart attack, although many believe that he was poisoned in an attempt to keep the Vatican ‘on side’.

All of which, of course, was strenuously denied by Vatican officials. Despite the suspicious circumstances of his death and calls for an autopsy, John Paul’s body was embalmed within one day. It was claimed at the time that a papal autopsy was prohibited under Vatican law, overlooking the fact that an autopsy had been carried out on Pope Pius VIII on his death in 1830, also allegedly of poisoning.

When John Paul II, the first Polish pope, assumed control following the sudden demise of his predecessor, funds from the Vatican and CIA began to be channelled via Banco Ambrosiano to Poland to support the burgeoning Solidarity Movement headed by the revolutionary shipyard worker (and later president) Lech Walesa.

Pope John Paul II made many speeches that were supportive of the Polish people, who were still, at that time, caught in the iron grip of the Soviet Union. As chairman of Banco Ambrosiano, the perceived conduit between the Vatican and the Polish revolutionaries, Calvi may well have made important enemies in Russia during this time.

After all, shortly afterwards an assassination attempt was made on the Pope himself in Vatican Square, thought to be a direct result of his interference in Eastern Europe.

Calvi, realizing he was in it up to his nail bag, is reported to have commented to a friend at that time: ‘The only book you’ve got to read is The Godfather. That’s the only one that tells you how this world is really run.’ But the net was finally closing in on organized crime in Italy. The Bank of Italy produced a report on an investigation into the activities of Banco Ambrosiano, concluding that bank officials had illegally exported several billion lire.

During the subsequent trial in 1981, Roberto Calvi was found guilty, fined nearly 20 million lire and given a suspended four-year prison sentence for siphoning 27 million lire out of Italy in violation of currency laws.

His P2 connections facilitated Calvi’s release on bail pending appeal and, remarkably, he even kept his position as chairman of Banco Ambrosiano but the banker insisted he was innocent of all charges and was being manipulated by others. During his spell in prison in 1981 prior to being tried, Calvi is known to have taken the unusual step of asking to see the magistrates hearing his case in the middle of the night.

The men duly obliged and Calvi said he would volunteer information about the funding of Italy’s political parties and their connection with both organized crime and the Roman Catholic Church. But he limited his information to a $21 million loan to the Socialist Party, and claimed he needed more time to gather further information and supporting evidence.

So at a stroke Roberto Calvi had made enemies of the Italian Socialist Party, organized crime and the Vatican, not forgetting the Russians, who viewed somewhat dimly his financial arrangements with Lech Walesa and his Solidarity Movement.

The following year, in June 1982, Banco Ambrosiano dramatically collapsed after it was discovered that between $700 million and $1.5 billion had been spirited away, much of it via Vatican sources and their Institute for Religious Works (commonly known as the Vatican Bank). Following the bank’s collapse, it came as no surprise that the Vatican agreed, in 1984, to pay $224 million in compensation to the 120 creditors of the failed bank.

Most of the compensation found its way to the island of Sicily, perhaps very wisely too in the circumstances. Extraordinarily, the Vatican managed to remain out of the scandal, citing its compensation payment as ‘recognition of its moral involvement’ in the bank’s collapse. Calvi himself was by now exceedingly twitchy, stating in a rare interview for La Stampa that he felt threatened. ‘In this sort of atmosphere any barbarity is now possible.

Many people have a lot to answer for in this affair,’ he said to the newspaper, before announcing cryptically, ‘I am not sure who yet, but sooner or later it will all come out.’ He went on to confide in his lawyers: ‘If the whole thing ever does come out, it will be enough to start the Third World War.’ Clearly a reference to the anti-Communist activities of the Vatican and P2 members.

Shortly afterwards, on 10 June 1982, Calvi disappeared from his Milan home, having shaved off his trademark moustache and acquired a false passport in the name of Gian Roberto Calvini. He was armed with cash in three currencies, including Swiss francs, indicating his intention to travel to that country, and a single black leather briefcase stuffed with documents.

A Calvi confidant from Sardinia, Flavio Carboni, who had recently been paid $11 million by Calvi to provide ‘security’ arrangements, then spirited the banker out of Italy using a speedboat, helicopter, eight private planes, three false identities and fourteen separate safe houses.

Roberto Calvi must have been exhausted by the time he checked into Chelsea Cloisters residential hotel in London on 13 June. He was found hanging under the bridge only five days later.

Against this background of intrigue on an international scale, it is extraordinary that a British coroner concluded that – despite the middle-aged banker suffering from vertigo and requiring the agility of an Olympic gymnast to reach the position he was found hanging from under Blackfriars Bridge – Calvi must have committed suicide.

The fact that the only time anybody, short of said athlete, could reach that part of the bridge was at high tide, and by boat, seemed not to trouble the coroner; and neither did the bricks found in Calvi’s pockets, nor the small matter of his hands being tied behind his back.

And that’s not all. Any dust or other bits of debris that would have clung to Calvi’s clothing as a result of Calvi clambering along the scaffolding under the bridge was not taken into account. And neither was the medical evidence of Professor Keith Simpson, despite being the man who had pioneered forensic investigation, who concluded that Calvi had been strangled and not hanged, as there was no evidence of the type of neck injury associated with a drop.

The fact that police officers found enough barbiturates to fell an elephant in Calvi’s room at Chelsea Cloisters – suggesting that the banker could have committed suicide, painlessly, sitting comfortably in bed in his pyjamas and dressing gown, had he wanted to end his life – was also overlooked. Quite rightly, a second inquest overruled the first, but even this one only provided an open verdict. So, what did happen to him then? And why was all this evidence seemingly overlooked?

Towards the end, Calvi hadn’t known which way to turn. He had made many enemies, albeit without intending to, and, in Mafia terms, knew exactly where all the bodies were buried – perhaps quite literally. As we have seen, Calvi had become the financial link between the Mafia, the Vatican, P2 and the Italian state. Even the Russians wanted information from the banker. And those who didn’t need his help any more and felt he knew too much preferred him to be silenced for ever. He was a wanted man, whichever way he faced.

During the weeks prior to his death, Calvi had certainly been keeping dubious company, dangerous enough for investigators not even to glance in the direction of the Vatican to begin with. But Roberto Calvi had been a close associate of the powerful American archbishop Paul Marcinkus, head of the Vatican Bank and heavily involved in the international money movement effected by Banco Ambrosiano.

Marcinkus had been criticized by many in the Pope John Paul II’s inner circle and they had called for his removal. The Pope had swiftly closed ranks around Marcinkus, enabling the Vatican’s diplomatic status to protect him. Even when Italian authorities later issued arrest warrants for Marcinkus and two senior Vatican officials, declaring them ‘socially dangerous’ and demanding that, if apprehended, they be denied bail to prevent them fleeing the country, the limitless immunity of the Vatican gave them safe sanctuary.

Five days before his own disappearance, on 5 June 1982, Calvi wrote in desperation to the Pope. In a letter made public during recent years by Calvi’s family, the banker pleaded with the pontiff, declaring him to be his ‘last hope’. He also gave a thinly veiled warning that the collapse of his bank would ‘provoke a catastrophe of unimaginable proportions in which the Church will suffer the gravest damage’.

Calvi used the opportunity to remind the Pope, or perhaps inform him for the first time, of the assistance his bank had provided the Vatican in funding both political and religious dealings with power makers in the East and West and of the banks in south America he had created to channel Vatican funds to help halt the expansion of Marxist ideology on that continent.

Calvi felt betrayed by the Vatican, claiming he had been abandoned by ‘the authority for which I have always shown the utmost respect and obedience’. He ended by informing the Pope of financial irregularities in Vatican bookkeeping, presumably manipulated by Archbishop Marcinkus.

Could that letter, tacitly threatening to reveal Marcinkus’s fraud, have effectively signed Calvi’s death warrant, while investigators were all looking in other directions, at the Mob and Propaganda Due? Casting blame upon P2 does make a great alternative conspiracy theory. After all, P2 members were believed to have addressed each other as ‘friar’.

Could this be why the ‘Black Friar’ (‘black’ because he had betrayed his fellows Masons) was found hanged at Blackfriars Bridge in London? The bricks in his pockets were certainly a Masonic symbol. Furthermore, new members are warned that betrayal of P2 secrets would result in death by hanging and the cleansing of the corpse by the tides.

Certainly Calvi had suggested to investigators that he was prepared to peel back the clandestine layers of P2’s skin. But would ‘punishing’ one of their number so publicly, in the middle of one of the world’s busiest cities, and with such overt symbolism, be worth the risk? Possibly not, as the Italian government disbanded the Masonic lodge shortly afterwards. At a stroke, the century-old secret society vanished, although many believed this was simply a cover-up for the Calvi killing as plenty of P2 members were also members of Parliament.

The Mafia were also heavily implicated in Calvi’s death. Indeed they had lost the most in his money-laundering disaster and mobster Flavio Carboni featured as a key figure during the final stages of Calvi’s life. From the beginning of 1982, the little Sardinian, who once boasted he would become the richest and most powerful man in Italy, became his constant companion and security adviser.

The relationship renewed Calvi’s access to real power, via Carboni’s secret-service connections, and the banker felt it could afford him some protection. He understood the advantages of hidden power, such as the Mafia and Propaganda Due possessed, but was also well aware of the downside of losing favour.

As the infamous American Mafioso informer commented to US officials when he broke the omertà (Mafia code of silence): ‘It is time I left our government and joined your government.’ Calvi was on the brink of doing the same, and expected Flavio Carboni to be the man who could enable it.

On 27 April 1982, the deputy chairman at Banco Ambrosiano, Roberto Rosone, left home for his office at 8 a.m. As he stepped into the street, a man with a pistol emerged from a doorway and fired directly at him, wounding Rosone in each leg. But armed guards posted at the Rosone residence had been alert to the possible danger and immediately returned fire, killing the would-be assassin outright.

Was Calvi trying to rid himself of those around him who knew too much about his activities, or, instead, was the net closing in on him? What is known is that the banker rushed to the hospital bedside of his deputy with the customary bunch of grapes – in this case trodden, fermented and presented in a bottle – and is reported to have exclaimed: ‘Madonna! What a world of madmen.

They are trying to frighten us, Roberto, so that they can get their hands on a group worth 20,000 billion lire.’ Calvi was said to be shocked to hear later that the would-be murderer had been identified as the feared Roman gangland figure Danilo Abbruciati, who emerged as a key Carboni ally when it later became known that, the day after the shooting, Carboni had paid an associate of Abbruciati, Ernesto Diotavelli, $530,000.

Flavio Carboni was soon in possession of a Calvi-funded cool $11 million, safely hidden away in a Zurich bank account, and a cigarette smuggler called Silvano Vittor was then employed as Calvi’s personal bodyguard. Vittor, Carboni and Calvi all met up in Zurich five weeks after the shooting and Calvi was smuggled to Austria where he boarded a private jet to London disguised as an executive of Fiat Motors.

In London, Calvi thought he would be safe and would be able to meet with the Italian magistrates to provide them with detailed information about the international money laundering by both the Mafia and the Vatican Bank in return for immunity from prosecution. But, instead, the very men he had paid to look after him delivered the banker into the hands of London Mob boss Francesco De Carlo, a seemingly respectable banker otherwise known as Frankie the Strangler.

Ironically, it was the Mafia themselves who would eventually solve the mystery of the death of ‘God’s Banker’. During the bloody Mafia war of 1981–3, as in-fighting rose to new levels of viciousness – entire families being wiped out to avenge acts of disloyalty both real and imagined – several high-ranking mobsters in both Italy and America, once safely under arrest, became valuable informers.

More – Albert Jack’s Mysterious World

In July 1991, one of these, Francesco Marino Mannoia, testified by video link from America (where he was living on a US witness protection programme) that he had been told on two separate occasions that the death of Roberto Calvi was murder, not suicide:

‘I remember I was on the run at the time and hiding at a villa in the countryside when news of Calvi’s suicide in London appeared on the television. With me at the time was Ignazio Pullara [a member of the Mafia] who told me in a very excited manner that he knew Calvi had been murdered. Then, a while later when I was in jail in Trapani, Sicily, I spoke to Ignazio’s brother Gio who also told me Calvi had been murdered by the Mafia. When I asked him why, I was told it was because he had been given a large amount of money from drugs and contraband cigarette sales to launder but he had failed to do so. After that he was considered to be no longer reliable and Cosa Nostra [the Sicilian Mafia] could not trust him any more.’

The Italian police subsequently re-opened the case and in 1998 they exhumed the body of Roberto Calvi. In 2002 new forensic methods confirmed the banker had indeed been killed and Roberto Calvi’s family were finally able to claim the $10 million the banker’s life had been insured for.

By then Frankie the Strangler was already in prison, but for other crimes. He had been given a 25-year jail sentence at the Old Bailey in 1987 after being captured following Britain’s largest-ever heroin smuggling bust. As he began his sentence in a maximum-security British prison, he listened in horror at the stories filtering back about the true extent of the Mafia war in the early 1980s, including the slaughter of women and children.

It was at this point that Frankie finally decided to start cooperating with anti-Mafia prosecutors. As he later told the court, ‘I just don’t want to be a part of Cosa Nostra any more.’

Other Mafia supergrasses, known as pentiti (‘those who have repented’), then came forward; one was another senior Mafia member called Antonio Giuffre, who confirmed to the police that the reason for the Mafia murdering Calvi was ‘poor money laundering’ and offered other information that directly led to the arrest, in 2004, of five people for the murder of Calvi.

These were Giuseppe ‘Pippo’ Calo, a convicted gangster; Flavio Carboni and his former girlfriend, Manuela Kleinzig, who was charged with providing Carboni with a false alibi; Silvano Vittor (Calvi’s bodyguard in London); and Ernesto Diotallevi, the head of the most dangerous criminal network in Rome and the man paid $530,000 the day after Calvi’s deputy had been shot in Milan.

Carboni immediately protested to the Italian newsagency Apcom that Roberto Calvi had close links to the Vatican and suggested the financier may have been killed on orders from the Church. Pointing the finger of blame directly at Archbishop Paul Marcinkus, he stated, ‘Perhaps the Vatican would have wanted him [Calvi] dead, but I didn’t.’

However, by the time of the arrests, Paul ‘the Gorilla’ Marcinkus was back in America leading a quiet life and still protected by Vatican diplomatic immunity. He has never spoken about his time in charge of the Vatican Bank. In fact, Marcinkus never said a word about anything right up until his death in 1990 – of ‘undisclosed causes’.

At the pre-trial hearings in December 2005, De Carlo, speaking from behind a security screen, explained how at the time of Calvi’s death he had been travelling from London to Rome: ‘A few days before Roberto’s death I heard that Bernardo Brusca [a leading Sicilian family member] wanted to see me. I also heard Pippo Calo wanted me to “do something for them”.’

He continued: ‘But when I saw them a few days later they told me things had been taken care of and they didn’t need me after all. I didn’t ask what they had wanted me for, it didn’t seem necessary. Calo just kept saying that a problem had now been resolved. That is how it works in the Mafia. We never said anybody had been killed, we just say a job has been taken care of.’

So, a quick recap then. We have the murder of Roberto Calvi following the collapse of Italy’s leading independent financial institution; we have the shooting of the bank’s deputy chairman, Roberto Rosone, and the death of his would-be assassin, the Roman gangster Danilo Abbruciati.

Then we have the payment, the day after the shooting, of $530,000 to Abbruciati’s lieutenant Ernesto Diotavelli by Calvi’s friend Carboni, who both now stand accused of murdering Rosone’s boss. In addition, we have characters such as Frankie the Strangler and Marcinkus ‘the Gorilla’.

Other elements of the story include the Vatican’s involvement in international money laundering and even in the suspected murder of Pope John Paul I, who may have threatened to reveal the truth. In 1986 Calvi’s black leather briefcase, containing all his secrets, turned up and the Vatican bought it without explanation – for $40 million.

A London-based Italian antiques dealer, said to be about to reveal the identity of Calvi’s killers to London police investigators, was himself murdered in 1982. We have Propaganda Due, the secret Masonic lodge whose members – including prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, who was certainly involved with Roberto Calvi – benefited from the fraud Calvi assisted the Vatican with.

At the time of writing, the only defendant in court to hear the charges being presented has been Flavio Carboni, who later told Sardinian journalists: ‘I know as much about Calvi’s murder as I do about the killing of Jesus Christ.’

On June 6, 2007, after nearly two years of hearing evidence, argument and the detailed defence of the five standing trial, the presiding judge, Mario Lucia d’Andria sensationally drew an end to the proceedings when he three the case out of court, arguing ‘insufficient evidence.’ However, the court did rule that Roberto Calvi’s death should be treated as murder and not suicide.

A conclusion that asked more questions than it answered. Legal experts argued that there were many people, including senior mafia members and Vatican officials who had a clear motive for Calvi’s murder and who would benefit fro his silence.

Observers also noted that as twenty five years had passed, since the hanging banker had been discovered, prosecutors had found it almost impossible to present a credible case. After all, key witnesses had been either unwilling to testify, unable to be found or were no longer alive.

The Calvi family’s private investigator, Jeff Katz, claimed that senior figures, both commercial and political, had escaped attention and to bring evidence against them would be impossible. He also conceded that it was ‘likely’ that the Mafia had been involved but suspects were either dead or missing.

The surprise verdict failed to put an end to the matter as the Roman prosecutor’s office opened a second investigation naming others, some of whom were already serving life sentences on unrelated matters.

On May 7 2010 there were further acquittals due to lack of evidence and on November 8 2011 the Court of the Last Resort, better known as the Court of Cessation, confirmed the acquittals and closed the files.

There is now very little, if any chance at all, that the mysterious death of the financier found hanging under Blackfriars Bridge miles from his native land, will ever be solved. Although we all have our own suspicions, don’t we. – Albert Jack

Albert Jack AUDIOBOOKS available for download here

Albert Jack’s Mysterious World